Diane comes back to a simple prescription: We should pursue business as usual with a few extensions of current policy. Unfortunately that is not serving us well, because this is exactly what we have done for several decades. We have developed a system that pays little attention to students and their achievement but that supports any adult who has found a job in schools. This policy does not look good by historical evidence on student outcomes. But it is common to defend this basic lack of management by throwing in red herrings whenever any policy change is suggested.

Once more through the evidence:

We have clear and consistent estimates about the variation in teacher effectiveness that exists in schools. The information comes from information on student test scores – something that is directly related to future student earnings and to the aggregate performance of the economy.

Differences in skills on tests of math, science, and reading lead to stunning differences in economic outcomes. Economic outcomes are not everything. But, as we have a continued national debate about both our international competitiveness and the fate of the bottom of the income distribution, we should not ignore economic outcomes.

Undoubtedly other, unmeasured things beyond test scores are also important to students and to society, but there is no reason to believe that being good in these other things is hurt by having greater measured skills. And there is no reason to believe that teachers at the bottom in terms of producing measured skills are anything but the bottom in producing useful unmeasured skills.

It is a red herring to say there might be unmeasured other things that are also important.

Further, there is now consistent evidence that ratings by principals (on metrics other than test scores) are highly correlated with ratings on test scores at the top and bottom of the distributions. While there is confusion in the middle, there is not confusion at the top and bottom.

It is a red herring to say that different evaluation systems produce different results.

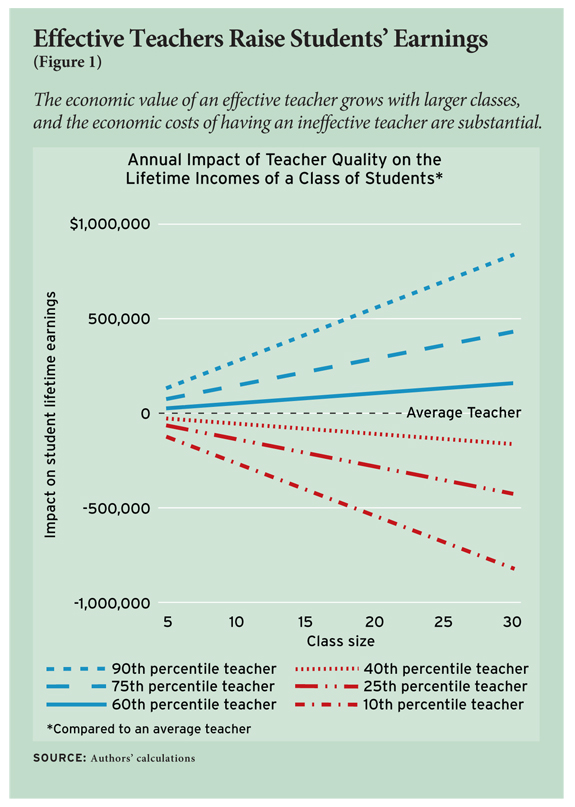

If we put together the impact of good teachers on student achievement and the impact of achievement in the lifetime earnings of students, we find that a good teacher (one in the top quarter in terms of effectiveness) each year produces over $350,000 more income for her students compared to an average teacher. But, symmetrically, a teacher in the bottom quarter subtracts $350,000 in income each year of teaching compared to an average teacher.

Ignoring these differences leads to huge inequities and to enormous waste in the potential of our students. I personally think the stakes are large enough that we should consider something other than business as usual.

As Diane points out, I have always advocated other policies that support the improvement of our teaching force: better mentoring, improved professional development, well designed curricula, complementary technologies, and so forth. But, my interpretation of the evidence is simply that none of these policies has been very successful at improving the least effective teachers. Further, our “best” teacher development policies do not go to scale up very well and are not systematically chosen by districts.

It is a red herring to point to other, complementary policies for improving teacher effectiveness without acknowledging the importance of starting with effective teachers.

Finally, it is fine to talk about teacher turnover, but not all teacher turnover is bad. If we move a bad teacher out of a school serving disadvantaged students, it is not a bad thing. The turnover rate in teaching is no different from that in other professions, and the initial turnover in teachers should not be used as a reason for ignoring the effectiveness of teachers. There is an excess supply of potential teachers. The shortage is not teachers per se but effective teachers.

It is a red hearing to say that teacher turnover is high without considering the implications for teacher effectiveness and ultimately for student achievement.

It is unfortunate that the “applause lines” to which Diane gravitates tend to be red herrings, distracting us from the national imperative to improve the effectiveness of our teacher force. I have focused on one specific policy – eliminating the teachers that are harming our children. Diane wants to introduce the idea that, while there are teachers who are harming kids, we should not deal with them because there might be some residual uncertainty about the very last teacher who is in this group.

She repeatedly use the word “firing” to conjure up images of large, unjust, and arbitrary actions. To the contrary, it is simply good management to move a very small number of ineffective people out of the front line of schools. And by so doing, it acts to elevate the status of the vast majority of effective teachers.

Policy by red herring seldom leads to good policy. It certainly does not when considering teacher policy. Diane is very skillful at distracting us from issues of student achievement, but avoiding those issues will be very costly to the nation.

[Note: this is the second part of an exchange on teacher policy with Diane Ravitch.]